Posted: 2006-10-05 05:03pm

Whoa, new page. I'm so taking advantage of this.

An Abriged History of the Philippines

The Independence of the Philippines

In the years leading-up to the Great War, Spain suffered from much political turmoil. In 1830 King Fernando VII de España, finding himself with no male heir, issued a Pragmatic Sanction that would allow his eldest daughter to become reigning Queen upon his death. In 1833, Fernando died, and his wife Maria Cristina de Borbon-Dos Sicilias became regent on behalf of their infant daughter Isabel II.

The Pragmatic Sanction had robbed Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, Fernando's brother, of his title as Principe de Asturias. Capitalizing on resentment among conservatives against Ferninand's recent liberal reforms, he styled himself Carlos V and set off to war. During the seven-year conflict, the Carlists dominate large rural areas but fail to capture a single important city, port, or industrial area. Naturally, they lose.

In 1845, Carlos V abdicates in to his son Carlos Luis de Borbón, who takes the title of Carlos VI and initiates the Second Carlist War when Isabel II does not marry him. It was more of a failure than the first, consisting mostly of guerrilla actions in the East of the country that accomplished nothing. Fighting lasted from 1846-'49.

In 1860, Carlos V is taken prisoner and abdicates to his younger brother Juan, who takes the title Juan III. What would have become the Third Carlist War is engulfed into the myriad of wars and conflicts known simply as the Great War. In terms of military gains, the Third Carlist War was considerably more successful than the other two. However, in terms of still having a pretender to throne after they lost, it was a spectacular failure. By the end of it, the Carlists are charred and rotting corpses, strewn across battlefields in Eastern Spain and Southwestern France.

The turmoil and chaos of the Great War caused many monarchs to lose their heads, both figuratively and literally. In an attempt to preserve the Spanish Burbon line and crown, should the worst happen, Isabel II sent her eldest daughter to the Philippines. In 1867, the young Isabel arrives and takes control of the colony in the name of her mother the Queen. Sent there to establish a place to retreat to in the event of Spain's fall, the Infanta takes nominal control of all Spanish oriental units and begins to consolidate her authority over the Philippines. This effectively makes them semi-autonomous.

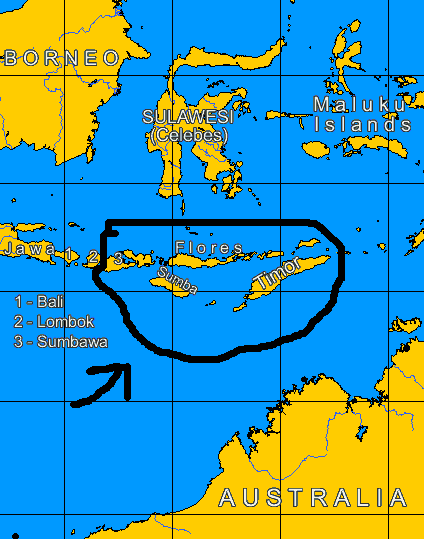

By the late 1870s, Europe is still burning. In Spain, Isabel II and most of the Burbon family lies dead. Alfonso XII, Prince of Asturias, takes the Spanish crown. Spain, like most of Europe, has been devastated by endless war; the scraps of its Empire in the West were lost when the War Between the States spilled into Caribbean; however, the colonies in the Eastern Indies continue to hold under the able leadership of Isabel. Against the councel of his advisors, Alfonso sends word to his older sister that he, as her King, orders her to declare the Philippines and other oriental colonies independent from Spain and install herself as their Queen. On the 11-year anniversary of her arrival, the Phillipine General Court approves the Infanta's claim to the title of Isabel III, Queen of the Philippines.

Interlude

In the early 1800s, a member of the Nipponese noble family Saionji found himself yearning for adventure and excitement. Nipponese tradition and culture emphasizes duty and honor, but some people are unperturbed by even the strongest of societal bounds. This young man, named Raizo, decided that doing the duties expected of him was not the kind of life he wanted to lead. Determined to forge his own destiny, he simply left his home and homeland, leaving behind only a short letter explaining why.

The next two decades of this Raizo's life were certainly full of excitement, action, and adventure. Specifically, the kind of excitement, action, and adventure that is generally illegal and tends to require proficiency in the use of personal weapons. That is not to say he was a complete villain, just that it's hard to (for example) praise the destruction of a slave-trade operation when it was done for fun and profit. Well, at least from moral standpoint. The sheer brilliance of the plan, near perfect coordination of assets, as well as intelligent usage of both rival syndicates and the law as pawns to accomplish objectives is certainly worthy of admiration.

After having enough excitement to last a couple of lifetimes, he decided to settle down. It probably was not a desire for a change of pace, though the life he lead was not well suited for a man pushing 40. The reasons for his retirement from swashbuckling were a beautiful Philippino girl in her mid-20s, and one too many scrapes with death. He married the girl, despite the vociferous objections of her family, and acquired a home in Manila.

The profit margins in certain illegal trades are very high because of the high risk factor. Because of this, Raizo' swashbuckling days had been very profitable. Using the small fortune he had amassed, Raizo entered the world of business, a world that he found many of his skills to be very well suited to. He began to invest in the growing coal mining industry in Luzon, as well as several other enterprises. As the years wore on, Raizo's wealth and power grew. It wasn't long before his wife's family was praising her for finding such a good husband.

Raizo spent the rest of his days running his business, occasionally using his influence in politics, and enjoying his wealth.

Isabel III

The oldest daughter of Isabel II was an intelligent and able leader. During the years after her arrival to the Philippines, she deftly dealt with diplomatic, economic, and military issues. She is behind the foundation and framework upon which much of the modern industry, government, and society in the Philippines are built.

She did not do this by herself. Many entrepreneurs, government officials, and common people were important contributors to the modernization of the island chain. However, there are two men in particular who are vital to analyzing both Isabel's efforts to modernize the Philippines, and the woman herself. One was a prominent and powerful entrepreneur, the other his son and heir.

It was inevitable that once Isabel got to the Philippines she would meet Raizo Saionji. She was the crown-appointed governor, and he a man of great power and influence. Their interests overlapped in many areas, it would have been impossible for either of them to conduct business without having to deal with the other. They quickly found that it benefited the both of them to work in synergy rather than opposition. Together, they established and secured a great economic and political power base in the island chain.

Raizo put his second son Shiro in charge of negotiating with government and, more importantly, Isabel herself. He even made sure to arrange that the two often met personally to discuss business. It is unclear if he did more than that, but it was not long before Isabel and Shiro were finding excuses to see each other, like personally delivering messages or coming to clarify minor issues, simple things that could have been handled by assistants. Shortly thereafter, they stopped pretending it was all business.

In early 1870, the Infanta Isabel informed Raizo that she was marrying his son. It made him smile, back in Nippon such a thing would have been preposterous. They did not talk for long, but it is not hard to guess what they talked about. The fact of the matter is that Raizo’s machinations were unnecessary, all he needed to do was suggest that Isabel and his son marry, she would have readily agreed. There were obvious net political and economic benefits. However, he preferred his son to marry of his own free will. At the very least, if he didn’t fall in love with Isabel, Shiro would be marrying a friend, a person he liked and got along with. Shiro did fall in love with the brilliant and assertive ruler of the Philippines; it was Isabel who married a friend in the name of political expedience and power consolidation. However, she did grow to love him as the years passed.

The news of the marriage had mixed reactions among the populace. The conservatives and royalists were horrified at seeing a European of royal blood marry an Asian man. Philippinos, particularly those with nationalist inclinations, were elated to see her marry someone who they largely considered one of their own. Her supporters liked the prospect of her getting a firmer grip on the islands, her opponents didn’t. All told, Isabel’s approval rating went down considerably, but there was much partying in the streets.

The Moro Rebellion

The morning of April 11, 1884. As Queen Isabel makes her way to the General Court, a man steps in front of her carriage brandishing a strange flag. When the guards move to apprehend the intruder, a second man rushes the carriage from the side and detonates. Although shaken by the explosion, Isabel is uninjured, her armored carriage able to withstand the explosion and debris. The Queen steps out to help the various injured guards and civilians. A mistake, made evident when a third assailant runs out of the crowd. A sharp-eyed guard sees him first and shoots. The assassin crumples, but as he falls he hurls a package into the air. It tumbles end over end in an arc heading toward the Queen, and then all Hell breaks loose.

Within two hours of the assassination attempt, Llanao del Sur, Maguidanao, and the Sulu Archipelago districts erupt in open rebellion. Armed with knives, swords, spears, and rifles both muzzle and breech-loaded, hordes of peasants attack garrisons and government offices. This is followed by uprisings in the Zamboanga and SuCCSKSarGen provinces. Within days, hours in some places, the Crown’s entire government and military infrastructure in the southeastern parts of the Philippines is in full retreat.

The second bomb exploded in the air a few meters away from the Queen. Some citizens managed to secure a carriage and her guards rushed Isabel to a nearby hospital. Surgeons where able to treat many of her injuries, but the hemorrhaging was too much. She regained full consciousness in time to see her last sunset and say goodbye to her husband and children. Queen Isabel III of the Philippines is declared dead at 7:14 pm.

At 7:17 pm on April 11, 1884, Adrian Luis Alfonso Isabel de Borbón y Saionji, the Queen’s eldest child and chosen successor, bluntly informs everyone that he is now King. His impassive expression belies the previous grief-stricken countenance, and the teary faces of his family. It is widely believed that during the next year and a half he only shows emotion once. After ordering his father to convene the General Court to make the transfer of power official, and telling a trusted aide to deal with the funeral arrangements, the new King leaves the hospital and heads for the Comando Central de las Fuerzas Armadas.

[still incomplete, my Mary-Sue has to put down that rebellion]

An Abriged History of the Philippines

The Independence of the Philippines

In the years leading-up to the Great War, Spain suffered from much political turmoil. In 1830 King Fernando VII de España, finding himself with no male heir, issued a Pragmatic Sanction that would allow his eldest daughter to become reigning Queen upon his death. In 1833, Fernando died, and his wife Maria Cristina de Borbon-Dos Sicilias became regent on behalf of their infant daughter Isabel II.

The Pragmatic Sanction had robbed Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, Fernando's brother, of his title as Principe de Asturias. Capitalizing on resentment among conservatives against Ferninand's recent liberal reforms, he styled himself Carlos V and set off to war. During the seven-year conflict, the Carlists dominate large rural areas but fail to capture a single important city, port, or industrial area. Naturally, they lose.

In 1845, Carlos V abdicates in to his son Carlos Luis de Borbón, who takes the title of Carlos VI and initiates the Second Carlist War when Isabel II does not marry him. It was more of a failure than the first, consisting mostly of guerrilla actions in the East of the country that accomplished nothing. Fighting lasted from 1846-'49.

In 1860, Carlos V is taken prisoner and abdicates to his younger brother Juan, who takes the title Juan III. What would have become the Third Carlist War is engulfed into the myriad of wars and conflicts known simply as the Great War. In terms of military gains, the Third Carlist War was considerably more successful than the other two. However, in terms of still having a pretender to throne after they lost, it was a spectacular failure. By the end of it, the Carlists are charred and rotting corpses, strewn across battlefields in Eastern Spain and Southwestern France.

The turmoil and chaos of the Great War caused many monarchs to lose their heads, both figuratively and literally. In an attempt to preserve the Spanish Burbon line and crown, should the worst happen, Isabel II sent her eldest daughter to the Philippines. In 1867, the young Isabel arrives and takes control of the colony in the name of her mother the Queen. Sent there to establish a place to retreat to in the event of Spain's fall, the Infanta takes nominal control of all Spanish oriental units and begins to consolidate her authority over the Philippines. This effectively makes them semi-autonomous.

By the late 1870s, Europe is still burning. In Spain, Isabel II and most of the Burbon family lies dead. Alfonso XII, Prince of Asturias, takes the Spanish crown. Spain, like most of Europe, has been devastated by endless war; the scraps of its Empire in the West were lost when the War Between the States spilled into Caribbean; however, the colonies in the Eastern Indies continue to hold under the able leadership of Isabel. Against the councel of his advisors, Alfonso sends word to his older sister that he, as her King, orders her to declare the Philippines and other oriental colonies independent from Spain and install herself as their Queen. On the 11-year anniversary of her arrival, the Phillipine General Court approves the Infanta's claim to the title of Isabel III, Queen of the Philippines.

Interlude

In the early 1800s, a member of the Nipponese noble family Saionji found himself yearning for adventure and excitement. Nipponese tradition and culture emphasizes duty and honor, but some people are unperturbed by even the strongest of societal bounds. This young man, named Raizo, decided that doing the duties expected of him was not the kind of life he wanted to lead. Determined to forge his own destiny, he simply left his home and homeland, leaving behind only a short letter explaining why.

The next two decades of this Raizo's life were certainly full of excitement, action, and adventure. Specifically, the kind of excitement, action, and adventure that is generally illegal and tends to require proficiency in the use of personal weapons. That is not to say he was a complete villain, just that it's hard to (for example) praise the destruction of a slave-trade operation when it was done for fun and profit. Well, at least from moral standpoint. The sheer brilliance of the plan, near perfect coordination of assets, as well as intelligent usage of both rival syndicates and the law as pawns to accomplish objectives is certainly worthy of admiration.

After having enough excitement to last a couple of lifetimes, he decided to settle down. It probably was not a desire for a change of pace, though the life he lead was not well suited for a man pushing 40. The reasons for his retirement from swashbuckling were a beautiful Philippino girl in her mid-20s, and one too many scrapes with death. He married the girl, despite the vociferous objections of her family, and acquired a home in Manila.

The profit margins in certain illegal trades are very high because of the high risk factor. Because of this, Raizo' swashbuckling days had been very profitable. Using the small fortune he had amassed, Raizo entered the world of business, a world that he found many of his skills to be very well suited to. He began to invest in the growing coal mining industry in Luzon, as well as several other enterprises. As the years wore on, Raizo's wealth and power grew. It wasn't long before his wife's family was praising her for finding such a good husband.

Raizo spent the rest of his days running his business, occasionally using his influence in politics, and enjoying his wealth.

Isabel III

The oldest daughter of Isabel II was an intelligent and able leader. During the years after her arrival to the Philippines, she deftly dealt with diplomatic, economic, and military issues. She is behind the foundation and framework upon which much of the modern industry, government, and society in the Philippines are built.

She did not do this by herself. Many entrepreneurs, government officials, and common people were important contributors to the modernization of the island chain. However, there are two men in particular who are vital to analyzing both Isabel's efforts to modernize the Philippines, and the woman herself. One was a prominent and powerful entrepreneur, the other his son and heir.

It was inevitable that once Isabel got to the Philippines she would meet Raizo Saionji. She was the crown-appointed governor, and he a man of great power and influence. Their interests overlapped in many areas, it would have been impossible for either of them to conduct business without having to deal with the other. They quickly found that it benefited the both of them to work in synergy rather than opposition. Together, they established and secured a great economic and political power base in the island chain.

Raizo put his second son Shiro in charge of negotiating with government and, more importantly, Isabel herself. He even made sure to arrange that the two often met personally to discuss business. It is unclear if he did more than that, but it was not long before Isabel and Shiro were finding excuses to see each other, like personally delivering messages or coming to clarify minor issues, simple things that could have been handled by assistants. Shortly thereafter, they stopped pretending it was all business.

In early 1870, the Infanta Isabel informed Raizo that she was marrying his son. It made him smile, back in Nippon such a thing would have been preposterous. They did not talk for long, but it is not hard to guess what they talked about. The fact of the matter is that Raizo’s machinations were unnecessary, all he needed to do was suggest that Isabel and his son marry, she would have readily agreed. There were obvious net political and economic benefits. However, he preferred his son to marry of his own free will. At the very least, if he didn’t fall in love with Isabel, Shiro would be marrying a friend, a person he liked and got along with. Shiro did fall in love with the brilliant and assertive ruler of the Philippines; it was Isabel who married a friend in the name of political expedience and power consolidation. However, she did grow to love him as the years passed.

The news of the marriage had mixed reactions among the populace. The conservatives and royalists were horrified at seeing a European of royal blood marry an Asian man. Philippinos, particularly those with nationalist inclinations, were elated to see her marry someone who they largely considered one of their own. Her supporters liked the prospect of her getting a firmer grip on the islands, her opponents didn’t. All told, Isabel’s approval rating went down considerably, but there was much partying in the streets.

The Moro Rebellion

The morning of April 11, 1884. As Queen Isabel makes her way to the General Court, a man steps in front of her carriage brandishing a strange flag. When the guards move to apprehend the intruder, a second man rushes the carriage from the side and detonates. Although shaken by the explosion, Isabel is uninjured, her armored carriage able to withstand the explosion and debris. The Queen steps out to help the various injured guards and civilians. A mistake, made evident when a third assailant runs out of the crowd. A sharp-eyed guard sees him first and shoots. The assassin crumples, but as he falls he hurls a package into the air. It tumbles end over end in an arc heading toward the Queen, and then all Hell breaks loose.

Within two hours of the assassination attempt, Llanao del Sur, Maguidanao, and the Sulu Archipelago districts erupt in open rebellion. Armed with knives, swords, spears, and rifles both muzzle and breech-loaded, hordes of peasants attack garrisons and government offices. This is followed by uprisings in the Zamboanga and SuCCSKSarGen provinces. Within days, hours in some places, the Crown’s entire government and military infrastructure in the southeastern parts of the Philippines is in full retreat.

The second bomb exploded in the air a few meters away from the Queen. Some citizens managed to secure a carriage and her guards rushed Isabel to a nearby hospital. Surgeons where able to treat many of her injuries, but the hemorrhaging was too much. She regained full consciousness in time to see her last sunset and say goodbye to her husband and children. Queen Isabel III of the Philippines is declared dead at 7:14 pm.

At 7:17 pm on April 11, 1884, Adrian Luis Alfonso Isabel de Borbón y Saionji, the Queen’s eldest child and chosen successor, bluntly informs everyone that he is now King. His impassive expression belies the previous grief-stricken countenance, and the teary faces of his family. It is widely believed that during the next year and a half he only shows emotion once. After ordering his father to convene the General Court to make the transfer of power official, and telling a trusted aide to deal with the funeral arrangements, the new King leaves the hospital and heads for the Comando Central de las Fuerzas Armadas.

[still incomplete, my Mary-Sue has to put down that rebellion]